Private Property Rights allow people to fully own and employ their assets, land and resources—without interference from the government or any other entity or individual(s).

Property rights are natural rights: which is to say that every individual has an inalienable and moral right over one’s property—regardless of whether it is recognized or adequately protected by the state. Indeed, private property rights have existed since time immemorial—even before organized form of government came into existence. To quote French philosopher and economist Frederic Bastiat: “Life, liberty, and property do not exist because men have made laws. On the contrary, it was the fact that life, liberty, and property existed beforehand that caused men to make laws in the first place.”

To be sure, Indians do have a right to property. But for many Indians, the right is neither properly defined nor adequately protected. Apart from that, there exist several regulatory restrictions that prevent individuals from freely employing their property.

The lack of secure property rights and regulatory restrictions hurt the poorest among us.

While rich people living in cities have relatively secure titles to their property; the poor in India’s farms, villages and forests do not. If we can secure strong property rights for the poorest among us, it will go a long way in helping them to prosper and escape poverty. Property rights, for millions of Indians, are either not secure or are not well-defined. The following is worth noting-

Compulsory Acquisition: In the last few decades, the state has enlarged the scope of compulsory acquisition—displacing many in the process without adequate compensation or rehabilitation. This has been the source of a lot of discontent among the people, fuelling several grass root movements with people demanding their rights.

Insecure Titles: Millions of Indians lack a clear title to their land, and it is hard to establish your title even if you’ve been living on your land for years. For instance, the land rights of indigenous tribes were not recognized by the state—despite these people living in the land for generations. It is only recently that this historical injustice has been addressed to some degree, but many continue to have insecure titles

Poor Land Records and Administration: The state has not only failed in recognizing the land rights of many citizens, it has also failed in creating adequate mechanisms for people to establish their title. Land records are poorly maintained and are, for most part, not computerized. Land laws are numerous, cumbersome and hard to comply with. Our land administration is complicated and needs to be streamlined.

Importance

One of the determining factors of the prosperity of a country is the respect and protection it accords to the property rights of its citizens.

Property rights allow people to be entrepreneurial. And enterprise allows people to create wealth and prosper.The security of property allows people to pursue their enterprise. A farmer, for instance, would not grow crops, or further develop his land if he knows that his land faces the threat of being seized by the government. A businessman would not expand his business if he perceives a credible threat of his business being taken over by the state. Individuals would not undertake risks, or make investments in land improvements if they feel that their ownership can be challenged. In the absence of a secure system of property rights, enterprise is throttled. Indeed, the one determining factor of the prosperity of a nation is the respect and protection it accords to the property rights of its citizens.

Prosperity and Property

A number of reasons are proposed to explain the prosperity (or lack thereof) in different countries. The standard reasons proposed are a country’s endowment of natural resources, population density, geographical location, state spending in education and healthcare, cultural values and a variety of other factors. When we go on to examine each of these factors, none of them manage to adequately explain why some countries are rich while others remain poor. Take the case of Singapore and Hong Kong. Both countries are city states, virtually devoid of natural resources. Yet, they are some of the most prosperous regions in the world. The case of South Korea is particularly astonishing: after being devastated in the Korean War in the 1950s, it has today—in the space of a few short decades—emerged as one of the most developed nations in the world. There are then, many anomalies when it comes to development—countries that prosper despite the lack of resources (Hong Kong); and countries that do not despite being rich in oil (Argentina). Likewise, there are some countries with high population densities that perform better than countries with low populating densities. Anomalies abound.

What explains these anomalies?

To be sure, development is a complex play of a number of variables. But when we cut through the complexity—a definite pattern emerges. Countries that value property rights, prosper; countries that do not—don’t. What ultimately does explain the difference in the levels of prosperity between nations is the institutional framework a country adopts—the most fundamental of these institutions being private property and the rule of law. Institutions can be thought to be the laws and formal rules that govern our interactions with each other. Institutions determine (to borrow an expression from Douglass C North), the ‘rules of the game.’ If the rules are well-defined, definite and conducive to enterprise—people prosper. If the rules are uncertain, and do not protect people’s property, then people are prevented from prospering. In India, the rules or institutions that govern us are uncertain and restrictive. Further, the rules can be perverted by some—the rich and politically connected–for their benefit. If we are to affect real change, we need to tackle questions of how we can make our laws and institutions more just and inclusive. Today, the rules work against millions of India’s poor. While the rich have relatively secure titles to their property, the poor do not. We have regulatory restrictions that prevent the poor from freely employing their property and enjoying the fruits of their enterprise. If we are to secure justice and prosperity for all Indians, we need to make sure that the rules work for them. To quote Hernando De Soto, “The poor aren’t breaking the laws, the laws are breaking them.”

Reforms

As noted here India ranks a dismal 46 out of 97 countries examined in the 2014 edition of the International Property Rights Index (IPRI), behind many developing countries. There exist significant problems with our current property rights regime. Millions of Indians lack a clear, definite title—the titles are either not well-defined or not recognized by the government. (as is the case with tribals living in proximity to forests) The following are some of the major issues in India’s present property rights regime—

Lack of definite titles. Indiscriminate and excessive use of Compulsory Acquisition Lack of proper land administration Regulatory restrictions preventing individuals from freely employing their property (particularly ‘land use regulations.’)

Compulsory Acquisition:

In the last many decades, the state has enlarged the scope of compulsory acquisition—displacing many in the process without adequate compensation or rehabilitation. This has been the source of a lot of discontent among the people, fuelling several grass root movements with people demanding their rights.

Forcible land acquisition is considered to be the necessary price for economic growth and development. It is feared that if we do not resort to forcible acquisitions, large scale projects would not culminate as farmers would refuse to part with their land.

This fear, for most part, is misplaced. There are several projects that have culminated without state interference or resort to forcible acquisition. A notable example is the city of Gurgaon in Haryana, which was developed almost entirely without forcible acquisition. Likewise, if the prevailing laws did not create impediments for businesses to negotiate directly with the farmers; compulsory acquisition and state interference would not need to be resorted to.

There is another point to be noted here—the way property is held and the use to which it is put is decided by the people. As needs change, the ownership and the manner in which land is employed also changes. This decision is made by the people, and should not rest with the government bureaucrats. When these decisions rest with the bureaucrats, the resultant outcomes are neither just, nor economically efficient.

To be sure, there has been some restraint in the last few years in the scope of compulsory acquisitions with the coming of the new land acquisition law; but that has come with its own set of problems. The new bill shows no significant change in paradigm—it still holds land acquisitions to be inevitable. It only seeks to make the new law ‘more just and fair.’ But a law that is coercive and unfair to start with cannot be made ‘less coercive.’ The new law claims to be in the interest of the farmers—but does nothing to extend stronger property rights to them. In reality, the new bill simply creates impediments and bureaucratic hassles that would prevent businesses from directly negotiating with the farmers.

More than anything else, the land acquisition bill points to a larger problem. It is a testimony to the paradigm of development that we have come to follow—one that considers necessary and inevitable the fact of plunder that follows in its wake.

In a civilized society, the scope for coercion and forcible acquisitions needs to be minimal. Indeed, unless the circumstances are particularly compelling, there exists no moral case to forcibly acquire anyone’s property. In the last many decades, the state’s exercise of compulsory acquisition has been indiscriminate and excessive. The state should act neither as brokers, nor as agents of big businesses to negotiate with the farmers for them. The way forward should lie in minimizing the scope of acquisition and according stronger property rights to the farmers.

Land Use and Other Regulatory Restrictions

There exist several regulations that prevent individuals from freely employing their property. For instance, a farmer cannot sell his land for ‘non-agricultural purposes’ without obtaining the appropriate permissions. These ‘land use’ regulations severely depress the value and price of the land.

These regulations are supposedly in place to ‘protect the farmers.’ In reality, they are nothing but an avenue for corruption and misappropriating the property of the very farmers they are intended to protect.

Land use regulations do not only fail to serve the purpose they’re intended to serve—there exists no reasonable reason for their existence. The manner in and the uses to which land is employed reflects the changing needs of the people—as needs of people change, so does the way in which land is employed. For instance, as agricultural productivity increased, less land was required to feed the population, and this people began to instead employ this land in industry.

People, thus decide in the ways land is to be used. With laws and restrictions such as these, these decisions on the employment of land are instead taken by bureaucrats instead of the people. The decisions of the bureaucrats, of course, are taken on the grounds of political expediency instead of any objective assessment of the people’s needs. Likewise, several such regulations restrict what people can do with their land and property.

Land Titles not Recognized by the State

Millions of Indians lack a clear title to their land, and it is hard to establish your title even if you’ve been living on your land for years.

In many cases, the titles are not recognized by the government. This is true of the tribals and indigenous tribes living in proximity to forests. These tribals had been living on their land for centuries, but they were declared encroachers on their own land in British India. They were denied titles to their land and access to forest produce. Even after independence, the India government continued to deny forest dwellers the right to their land.

Only recently has this historical justice been somewhat rectified, with the passing of the Forest Rights Act (2005), which seeks to recognize the land titles of the forest dwellers. Even though the act created mechanisms for the tribals to establish and validate their titles; their claims were mostly rejected by the forest officials. However, with the active support of civil society organisations; the law has had some success in Gujarat. While the act acknowledges the rights of tribals and is a step forward in correcting this historical injustice; it has, for most parts of India, not been realized. (To learn more about the Forest Rights Act, Click Here)

Poor Land Administration

The current system of land administration has its roots in colonial India. The institutions and the processes developed since have only been slightly modified. Our present system of land administration needs to be reformed substantially.

For one, land records are maintained poorly and are not fully computerized. The lack of proper titling means that one’s claim on one’s property and land is not definite or conclusive. if one’s title is in conflict or not properly defined, one cannot employ it in productive outlets.

Our land administration needs an overhaul. We need to develop institutions and processes that are easily accessible and provide mechanisms to the people to definitely establish their land titles.

The economic costs of not having secure and defined property rights are enormous. The lack of property rights hurts people, and it hurts enterprise. None of these issues, unfortunately, are being seriously addressed by the government or our policy makers. The need of the hour, therefore, is a civil society movement that will systematically address these questions and bring these issues to the light of our government.

Current Situation

The ‘International Property Rights Index’ (IPRI) is an annual study published by ‘Property Rights Alliance’ (PRA) that aims to measure and compare the strength of property rights—both physical and intellectual—across 131 countries in the world. The study is conducted in collaboration with 74 think tanks and policy organizations involved in research, policy development, education and promotion of property rights in their countries. Since its inception in 2007, the index has come to empirically demonstrate the importance of secure property rights in economic development.

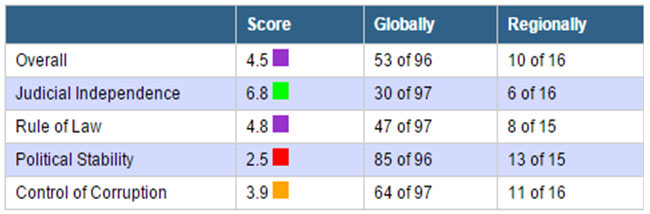

As part of its rigorous methodology, the IPRI measures the strength of the political and legal institutions of a country. Among other things, it takes into account the independence of the judiciary, the rule of law, the ease of securing credit and the legal protection extended to physical and intellectual property.

Additionally, the index factors in gender-based disparities in access to property, land and credit. For a detailed summary of the data methodology, Click Here and Click Here.

At present, India ranks a dismal 46 of the 97 countries that feature in the index. On a scale of 0 to 10, India has stagnated around 5.5 in the last 8 years. With respect to Intellectual Property Rights (IPR), India stands in at 50 of the 97 countries. There exist significant challenges in India’s property rights regime which need to be addressed.

India IPRI Ranking- 2014

Unfortunately, these discussions do not figure prominently in the public discourse and are neither manifest in the political will of the governments. While there is much talk about bringing in ‘economic reforms’, the most vital and basic of reforms of strengthening property rights somehow elude out political leaders.

For reading more about where India stands in this index, Click Here.